Spatial Fundamentals

Spatial Data Types

There are two primary types of spatial data: raster and vector data. Python and R can both handle either of these types so coding language doesn’t matter but there are fundamental structural differences between the two data types. See below for more information about each.

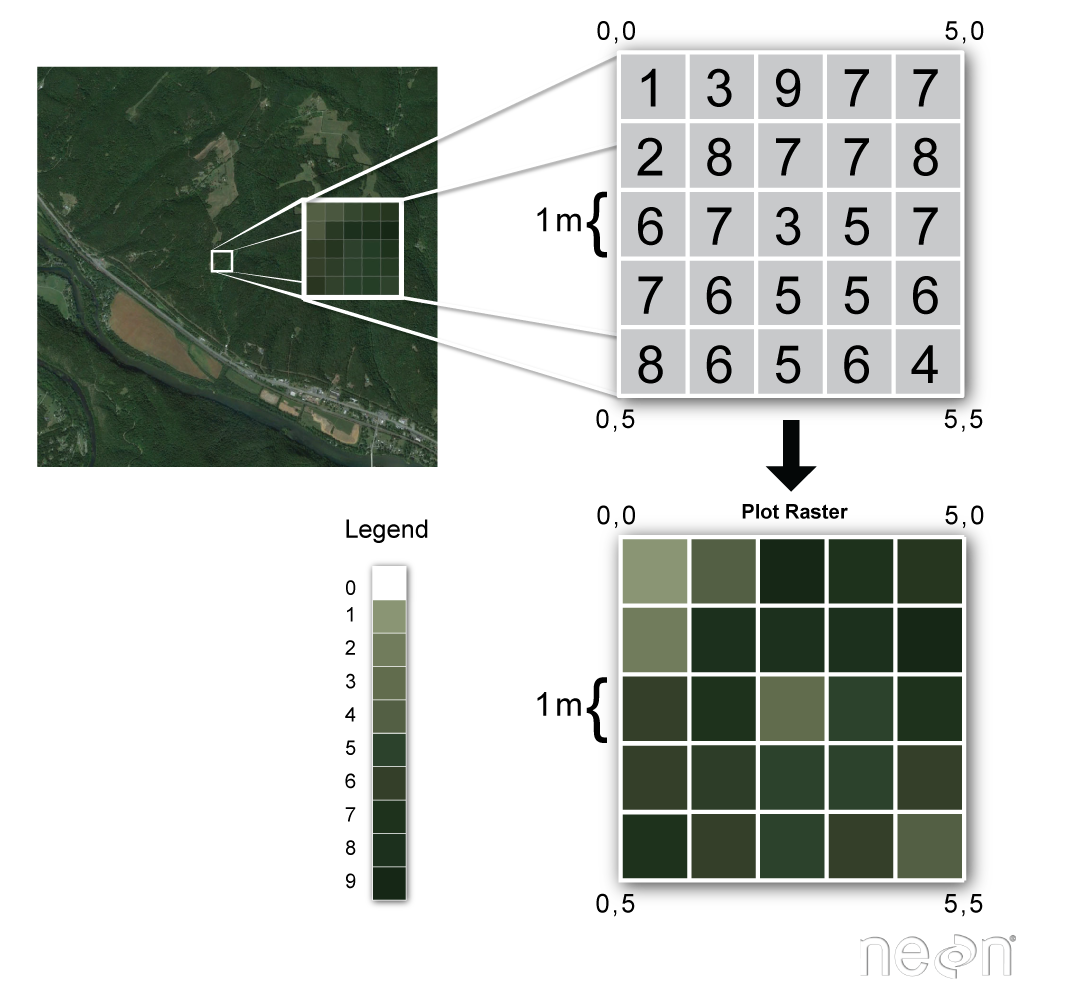

Raster data stores information in pixels. Each pixel is located at a specific geographic location (i.e., a specific X and Y coordinate pair). These pixel values can be continuous (e.g., rainfall, elevation, etc.) or categorical (e.g., land cover categories, date of first green up, etc.). Even if you’ve never worked with spatial data before you’ve certainly worked with rasters: technically every digital image is a raster!

Raster files are typically GeoTIFFs and use the .tif extension.

Consider this visual depiction of raster data:

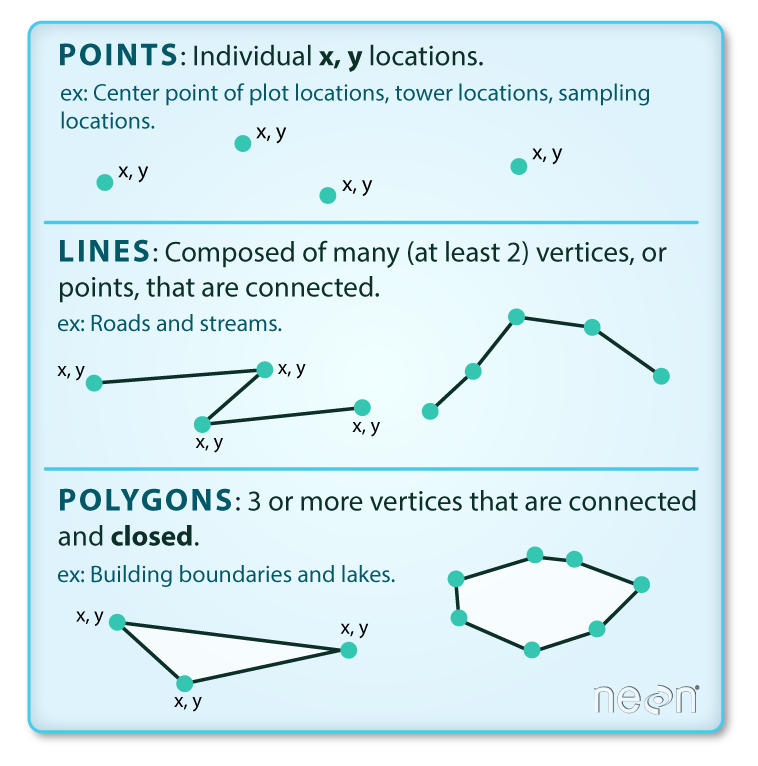

Vector data store information in “features”. These features use specific geographic points (again, think X and Y coordinates) and store information about the geometric relationship among features. This allows vector data to be in terms of particular geometries like points, lines, or polygons.

Vector data are typically preserved as shapefiles and use several extensions. When we refer to shapefiles in code we only refer to the .shp file but there are several associated files that must also be present in the same folder for the data to be read properly. These usually include .dbf, .prj, and .shx but there may sometimes also be a .xml file or two. For our purposes, the specifics of these files are not relevant but it is important to remember that you will need them in order to work with vector data.

Consider this visual depiction of vector data:

Coordinate Reference Systems (CRS)

While raster and vector data may both refer to non-spatial or spatial data, true spatial data requires a coordinate reference system (CRS). CRS has a very specific format that all geospatial applications (including Python and R!) use to display/process the data correctly. CRS includes three components:

- Datum – a model for the shape of the earth. It defines the starting coordinate pair and angular units that–when used with the starting point–define a particular spot on the planet. There can be global datums (e.g., WGS84, NAD83, etc.) that apply anywhere on the planet and local datums that work well for a particular area but do not work outside of that area

- Projection – mathematical transformation to get from a round planet to a flat map

- Additional Parameters – any other information necessary to support the projection (e.g., the coordinates of the center of the map, etc.)

A hopefully useful analogy is to consider the datum as a choice between a set of citrus fruits of varying shapes (e.g., lemon, orange, grapefruit, etc.) while the projection is a set of instructions on how to flatten the peel of the chosen fruit.

CRS Importance

Coordinate reference systems may sound dry and uninteresting–even in a pretty technical coding context–but they are vitally important! For many scientific purposes we want to know how a set of points intersect with a given map or how well several maps line up. To answer questions like these or interpret virtually any geospatial information, we must make sure that each spatial component uses the same CRS. Some coordinate reference systems use similar units which can mean a quick glance makes all spatial data seem interoperable while in reality the data cannot be directly compared without transforming to a standard CRS.

A rule of thumb that may help is that every spatial script you write should be very careful to check the CRS(s) used by the data.

Additional Resources

Spatial operations have gotten a ton of attention in both Python and R! This website is mostly focused on translating between the two languages though so much of this nuance is not covered here. For those interested in a deeper dive in spatial computing, consider the following.

- R – The Data Carpentries has a solid “Introduction to Geospatial Concepts” lesson

- R – Rachel King created a really nice “Spatial Data Visualization” workshop

- Python – The Arctic Data Center made a “Scalable and Computationally Reproducible Approaches to Arctic Resources” course that includes a “Spatial and Image Data Using GeoPandas” chapter